Ankle sprains are one of the most common joint injuries runners experience. The injury can occur when one rolls over a rock, lands off a curb, or steps in a small hole or crack in the road. Usually the sprain is only mild, but on occasion it may seriously injure the ligaments or tendons surrounding the ankle joint. Management of this injury relies on early and accurate diagnosis, as well as an aggressive rehabilitation program directed toward reducing acute symptoms, maintaining ankle stability, and returning the runner to pre-injury functional level.

General Anatomy of the Ankle

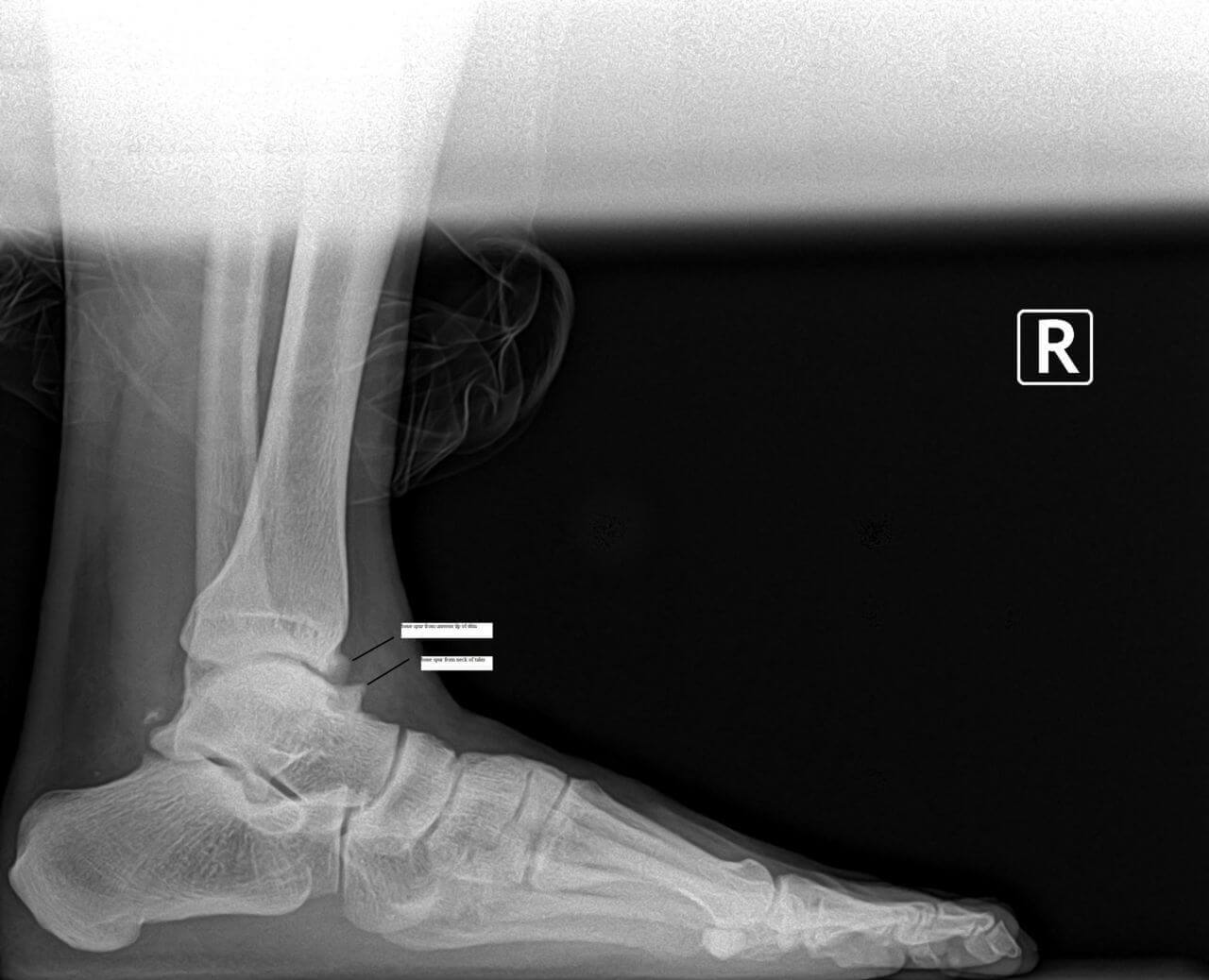

The ankle is comprised of three main bones: the talus (from the foot), the fibula and tibia (from the lower leg). The three bones together form a mortise (on the top of the talus), as well as two joint areas (on the inside and outside of the ankle), sometimes called the "gutters". The ankle is surrounded by a capsule, as well as tissue (the synovium) that feed it blood and oxygen.

Some of the more important structures that hold the ankle together are the ankle ligaments.

Most ankle sprains involving the ligaments are weight bearing injuries. When a runner's foot rolls outward (supinates) and the front of the foot points downwards as he or she lands on the ground, lateral ankle sprain can be a result. It is usually this situation that causes injury to the anterior talo-fibular ligament. However, when the foot rolls inwards (pronates) and the forefoot turns outward (abducts), the ankle is subject to an injury involving the deltoid ligament that supports the inside of the ankle. This can occur when another runner steps on the back of the ankle, as at the beginning of a race, or when a runner trips and falls on the runner in front of him.

Diagnosis

When assessing an ankle sprain, your podiatrist will want to know the mechanism of injury and history of previous ankle sprains. Where the foot was located at the time of injury, "popping" sensations, whether the runner can put weight on the ankle are all important questions needing an answer. If past ankle sprains are part of the history, for example, a new acute ankle sprain can have a significant impact.

The physical examination should confirm the suspected diagnosis, based on the history of the injury. One looks for any obvious deformities of the ankle or foot, black and blue discoloration, swelling, or disruption of the skin. When crackling, extreme swelling and tenderness are present, together with a limited range of motion, one may suspect a fracture of the ankle. A feeling of disruption on either the inside or the outside of the ankle may indicate a rupture of one of the ankle ligaments.

To check for ankle instability, the runner should be evaluated while weight bearing. Manual muscle testing is also valuable when checking for ankle instability. One of the more critical tests that a runner should be able to perform before allowing resumption of activity is a "single toe raise" test. If the runner is unable to do this, one might suspect ligamentous injury or ankle instability.

X-rays help rule out fractures, "fleck fractures" inside the ankle joint, loose bodies, and/or degenerative joint disease (arthritis). Stress X-rays are taken when ligamentous rupture or ankle instability is suspected. When a stress test is taken of your ankle, don't be surprised if the same test is performed on the other ankle. This is done to compare the two ankles, particularly in cases of ligamentous laxity (loose ligaments).

In the past, more commonly, ankle arthrography has been used. This involves injecting a dye into the ankle joint as it is X-rayed. This helps determine if a rupture of a ligament or tear of the ankle capsule has occurred. However, this procedure does involve some discomfort during the injection process, and, on rare occasions, an allergy to the dye occurs.

Other diagnostic tests include computerized tomography (CT Scan) to discover injuries of the bone, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to isolate and diagnose specific soft tissue injuries (ligaments, tendons, and capsule). The MRI is very specific, and gives a clear-cut view of these important structures.

Treatment

Treatment of an acute ankle injury usually begins with an aggressive physical therapy program that controls early pain and inflammation, protects the ankle joint while in motion, re-strengthens the muscles, and re-educates the sensory receptors to achieve complete functional return to running activity.

Modalities that decrease pain and control swelling include icing, electrical nerve stimulation, ultrasound, and/or iontophoresis patches. Easy, mild motion, with the limits of pain and swelling, can actually reduce the effects of inflammation. A continued passive motion (CPM) machine can be very helpful in decreasing pain and swelling.

Resumption of running activity is usually dependent on the runner's limits of pain and motion, and is begun to tolerance. As the runner improves, diagonal running can be prescribed. It is important to protect the runner with braces such as air casts, ankle braces, etc., which help to allow motion at the ankle joint under weight bearing.

Home exercise programs are very helpful for the post-ankle sprain runner. Proprioception re-education is critical for both the acute as well as the chronic ankle sprain. It may involve using a simple tilt board or more sophisticated proprioceptive training and testing devices.

For the acute grade III lateral ankle sprain, or complete deltoid tear, complete immobilization is usually recommended for at least four weeks. Afterwards, a removable cast is used to restrict motion and allow for physical therapy. If the ankle does not respond and ankle instability is diagnosed, surgical intervention may be required.

Today, ankle arthroscopy is a much less invasive procedure than other surgery and allows the ligament to be stabilized with tissue anchors. This eliminates an extended period of immobilization, joint stiffness and muscle atrophy. Post-operatively, this primary ligament repair is protected for approximately a two-to three-week period of time in either a cast or removable cast boot, with daily-continued passive motion, cold therapy, and controlled exercise.

At three weeks, a simple air cast or ankle brace is applied for an additional three weeks while therapy and rehabilitation is progressing. At six weeks, these devices are used only during running and other athletic activity as a safeguard. As the runner resumes strength and proprioceptive capabilities, the devices are discontinued.

Conclusion

When an acute or chronic ankle sprain is not treated, as unfortunately is all too often the case, repeated ankle sprains may occur. Because chronic ankle injuries do not show acute inflammation even when the ankle is weak and unstable, this may set the runner up for another ankle sprain when least suspected. A successive sprain may be more severe than the first, and cause an even more significant injury.

The most important point to keep in mind when talking about ankle injuries, then, is to prevent the condition from becoming chronic or recurrent.

So the next time you roll over that stone, or land in that small hole, make sure that your simple ankle sprain is just that: "simple".

If you don't want to have a swollen ankle all the time while running, don't ignore early warning signs. If you have any doubts about its seriousness, have your podiatrist check your injury.